Battle of Britain

***TOO LONG***The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (German: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force, the Luftwaffe. It has been described as the first major military campaign fought entirely by air forces. The British officially recognise the battle's duration as being from 10 July until 31 October 1940, which overlaps the period of large-scale night attacks known as the Blitz, that lasted from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941. German historians do not accept this subdivision and regard the battle as a single campaign lasting from July 1940 to May 1941, including the Blitz.

Mediterranean and Middle East

Other campaigns

Coups

1940

The Netherlands

Belgium

France

Britain

1942–1943

1944–1945

Germany

Strategic campaigns

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (German: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force, the Luftwaffe. It has been described as the first major military campaign fought entirely by air forces. The British officially recognise the battle's duration as being from 10 July until 31 October 1940, which overlaps the period of large-scale night attacks known as the Blitz, that lasted from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941. German historians do not accept this subdivision and regard the battle as a single campaign lasting from July 1940 to May 1941, including the Blitz.

The primary objective of the German forces was to compel Britain to agree to a negotiated peace settlement. In July 1940, the air and sea blockade began, with the Luftwaffe mainly targeting coastal-shipping convoys, as well as ports and shipping centres such as Portsmouth. On 1 August, the Luftwaffe was directed to achieve air superiority over the RAF, with the aim of incapacitating RAF Fighter Command; 12 days later, it shifted the attacks to RAF airfields and infrastructure. As the battle progressed, the Luftwaffe also targeted factories involved in aircraft production and strategic infrastructure. Eventually, it employed terror bombing on areas of political significance and on civilians.

The Germans had rapidly overwhelmed France and the Low Countries, leaving Britain to face the threat of invasion by sea. The German high command recognised the logistic difficulties of a seaborne attack, particularly while the Royal Navy controlled the English Channel and the North Sea. On 16 July, Hitler ordered the preparation of Operation Sea Lion as a potential amphibious and airborne assault on Britain, to follow once the Luftwaffe had air superiority over the Channel. In September, RAF Bomber Command night raids disrupted the German preparation of converted barges, and the Luftwaffe's failure to overwhelm the RAF forced Hitler to postpone and eventually cancel Operation Sea Lion. The Luftwaffe proved unable to sustain daylight raids, but their continued night-bombing operations on Britain became known as the Blitz.

Historian Stephen Bungay cited Germany's failure to destroy Britain's air defences to force an armistice (or even an outright surrender) as the first major German defeat in the Second World War and a crucial turning point in the conflict. The Battle of Britain takes its name from the speech given by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the House of Commons on 18 June: "What General Weygand called the 'Battle of France' is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin."

Background

Strategic bombing during World War I introduced air attacks intended to panic civilian targets and led in 1918 to the amalgamation of the British army and navy air services into the Royal Air Force (RAF). Its first Chief of the Air Staff, Hugh Trenchard, was among the military strategists in the 1920s, like Giulio Douhet, who saw air warfare as a new way to overcome the stalemate of trench warfare. Interception was nearly impossible, with fighter planes no faster than bombers. Their view (expressed vividly in 1932) was that the bomber will always get through, and that the only defence was a deterrent bomber force capable of matching retaliation. Predictions were made that a bomber offensive would quickly cause thousands of deaths and civilian hysteria leading to capitulation. However, widespread pacifism following the horrors of the First World War contributed to a reluctance to provide resources.

Developing air strategies

Germany was forbidden a military air force by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, and therefore air crew were trained by means of civilian and sport flying. Following a 1923 memorandum, the Deutsche Luft Hansa airline developed designs for aircraft such as the Junkers Ju 52, which could carry passengers and freight, but also be readily adapted into a bomber. In 1926, the secret Lipetsk fighter-pilot school began operating.Erhard Milch organised rapid expansion, and following the 1933 Nazi seizure of power, his subordinate Robert Knauss formulated a deterrence theory incorporating Douhet's ideas and Tirpitz's "risk theory". This proposed a fleet of heavy bombers to deter a preventive attack by France and Poland before Germany could fully rearm. A 1933–34 war game indicated a need for fighters and anti-aircraft protection as well as bombers. On 1 March 1935, the Luftwaffe was formally announced, with Walther Wever as Chief of Staff. The 1935 Luftwaffe doctrine for "Conduct of Air War" (Luftkriegführung) set air power within the overall military strategy, with critical tasks of attaining (local and temporary) air superiority and providing battlefield support for army and naval forces. Strategic bombing of industries and transport could be decisive longer-term options, dependent on opportunity or preparations by the army and navy. It could be used to overcome a stalemate, or used when only destruction of the enemy's economy would be conclusive. The list excluded bombing civilians to destroy homes or undermine morale, as that was considered a waste of strategic effort, but the doctrine allowed revenge attacks if German civilians were bombed. A revised edition was issued in 1940, and the continuing central principle of Luftwaffe doctrine was that destruction of enemy armed forces was of primary importance.

The RAF responded to Luftwaffe developments with its 1934 Expansion Plan A rearmament scheme, and in 1936 it was restructured into Bomber Command, Coastal Command, Training Command and Fighter Command. The last was under Hugh Dowding, who opposed the doctrine that bombers were unstoppable: the invention of radar at that time could allow early detection, and prototype monoplane fighters were significantly faster. Priorities were disputed, but in December 1937, the Minister in charge of Defence Coordination, Sir Thomas Inskip, sided with Dowding that "The role of our air force is not an early knock-out blow" but rather was "to prevent the Germans from knocking us out" and fighter squadrons were just as necessary as bomber squadrons.

The Spanish Civil War gave the Luftwaffe Condor Legion the opportunity to test air fighting tactics with their new aeroplanes. Wolfram von Richthofen became an exponent of air power providing ground support to other services. The difficulty of accurately hitting targets prompted Ernst Udet to require that all new bombers had to be dive bombers, and led to the development of the Knickebein system for night time navigation. Priority was given to producing large numbers of smaller aeroplanes, and plans for a long-range, four-engined strategic bomber were delayed.

The early stages of the Second World War saw successful German invasions on the continent, aided decisively by the air power of the Luftwaffe, which was able to establish tactical air superiority with great effectiveness. The speed with which German forces defeated most of the defending armies in Norway in early 1940 created a significant political crisis in Britain. In early May 1940, the Norway Debate questioned the fitness for office of the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. On 10 May, the same day Winston Churchill became British Prime Minister, the Germans initiated the Battle of France with an aggressive invasion of French territory. RAF Fighter Command was desperately short of trained pilots and aircraft. Churchill sent fighter squadrons, the Air Component of the British Expeditionary Force, to support operations in France, where the RAF suffered heavy losses. This was despite the objections of its commander Hugh Dowding that the diversion of his forces would leave home defences under-strength.

After the evacuation of British and French soldiers from Dunkirk and the French surrender on 22 June 1940, Hitler mainly focused his energies on the possibility of invading the Soviet Union. He believed that the British, defeated on the continent and without European allies, would quickly come to terms. The Germans were so convinced of an imminent armistice that they began constructing street decorations for the homecoming parades of victorious troops. Although the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, and certain elements of the British public favoured a negotiated peace with an ascendant Germany, Churchill and a majority of his Cabinet refused to consider an armistice. Instead, Churchill used his skilful rhetoric to harden public opinion against capitulation and prepare the British for a long war.

The Battle of Britain has the unusual distinction that it gained its name before being fought. The name is derived from the This was their finest hour speech delivered by Winston Churchill in the House of Commons on 18 June, more than three weeks prior to the generally accepted date for the start of the battle:

... What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilisation. Upon it depends our own British life and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of a perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, "This was their finest hour".

From the outset of his rise to power, Adolf Hitler expressed admiration for Britain, and throughout the Battle period he sought neutrality or a peace treaty with Britain. In a secret conference on 23 May 1939, Hitler set out his rather contradictory strategy that an attack on Poland was essential and "will only be successful if the Western Powers keep out of it. If this is impossible, then it will be better to attack in the West and to settle Poland at the same time" with a surprise attack. "If Holland and Belgium are successfully occupied and held, and if France is also defeated, the fundamental conditions for a successful war against England will have been secured. England can then be blockaded from Western France at close quarters by the Air Force, while the Navy with its submarines extend the range of the blockade."

When war commenced, Hitler and the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht or "High Command of the Armed Forces") issued a series of directives ordering, planning and stating strategic objectives. "Directive No. 1 for the Conduct of the War", dated 31 August 1939, instructed the invasion of Poland on 1 September as planned. Potentially, Luftwaffe "operations against England" were to "dislocate English imports, the armaments industry, and the transport of troops to France. Any favourable opportunity of an effective attack on concentrated units of the English Navy, particularly on battleships or aircraft carriers, will be exploited. The decision regarding attacks on London is reserved to me. Attacks on the English homeland are to be prepared, bearing in mind that inconclusive results with insufficient forces are to be avoided in all circumstances." Both France and the UK declared war on Germany; on 9 October, Hitler's "Directive No. 6" planned the offensive to defeat these allies and "win as much territory as possible in the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France to serve as a base for the successful prosecution of the air and sea war against England". On 29 November, OKW "Directive No. 9 – Instructions For Warfare Against The Economy Of The Enemy" stated that once this coastline had been secured, the Luftwaffe together with the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) was to blockade UK ports with sea mines. They were to attack shipping and warships and make air attacks on shore installations and industrial production. This directive remained in force in the first phase of the Battle of Britain. It was reinforced on 24 May during the Battle of France by "Directive No. 13", which authorised the Luftwaffe "to attack the English homeland in the fullest manner, as soon as sufficient forces are available. This attack will be opened by an annihilating reprisal for English attacks on the Ruhr Basin."

By the end of June 1940, Germany had defeated Britain's allies on the continent, and on 30 June the OKW Chief of Staff, Alfred Jodl, issued his review of options to increase pressure on Britain to agree to a negotiated peace. The first priority was to eliminate the RAF and gain air supremacy. Intensified air attacks against shipping and the economy could affect food supplies and civilian morale in the long term. Reprisal attacks of terror bombing had the potential to cause quicker capitulation, but the effect on morale was uncertain. On the same day, the Luftwaffe Commander-in-Chief, Hermann Göring issued his operational directive: to destroy the RAF, thus protecting German industry, and also to block overseas supplies to Britain. The German Supreme Command argued over the practicality of these options.

In "Directive No. 16 – On preparations for a landing operation against England" on 16 July, Hitler required readiness by mid-August for the possibility of an invasion he called Operation Sea Lion, unless the British agreed to negotiations. The Luftwaffe reported that it would be ready to launch its major attack early in August. The Kriegsmarine Commander-in-Chief, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, continued to highlight the impracticality of these plans and said sea invasion could not take place before early 1941. Hitler now argued that Britain was holding out in hope of assistance from Russia, and the Soviet Union was to be invaded by mid 1941. Göring met his air fleet commanders, and on 24 July issued "Tasks and Goals" of firstly gaining air supremacy, secondly protecting invasion forces and attacking the Royal Navy's ships. Thirdly, they were to blockade imports, bombing harbours and stores of supplies.

Hitler's "Directive No. 17 – For the conduct of air and sea warfare against England" issued on 1 August attempted to keep all the options open. The Luftwaffe's Adlertag campaign was to start around 5 August, subject to weather, with the aim of gaining air superiority over southern England as a necessary precondition of invasion, to give credibility to the threat and give Hitler the option of ordering the invasion. The intention was to incapacitate the RAF so much that the UK would feel open to air attack, and would begin peace negotiations. It was also to isolate the UK and damage war production, beginning an effective blockade. Following severe Luftwaffe losses, Hitler agreed at a 14 September OKW conference that the air campaign was to intensify regardless of invasion plans. On 16 September, Göring gave the order for this change in strategy, to the first independent strategic bombing campaign.

Hitler's 1923 Mein Kampf mostly set out his hatreds: he only admired ordinary German World War I soldiers and Britain, which he saw as an ally against communism. In 1935 Hermann Göring welcomed news that Britain, as a potential ally, was rearming. In 1936 he promised assistance to defend the British Empire, asking only a free hand in Eastern Europe, and repeated this to Lord Halifax in 1937. That year, von Ribbentrop met Churchill with a similar proposal; when rebuffed, he told Churchill that interference with German domination would mean war. To Hitler's great annoyance, all his diplomacy failed to stop Britain from declaring war when he invaded Poland. During the fall of France, he repeatedly discussed peace efforts with his generals.

When Churchill came to power, there was still wide support for Halifax, who as Foreign Secretary openly argued for peace negotiations in the tradition of British diplomacy, to secure British independence without war. On 20 May, Halifax secretly requested a Swedish businessman to make contact with Göring to open negotiations. Shortly afterwards, in the May 1940 War Cabinet Crisis, Halifax argued for negotiations involving the Italians, but this was rejected by Churchill with majority support. An approach made through the Swedish ambassador on 22 June was reported to Hitler, making peace negotiations seem feasible. Throughout July, as the battle started, the Germans made wider attempts to find a diplomatic solution. On 2 July, the day the armed forces were asked to start preliminary planning for an invasion, Hitler got von Ribbentrop to draft a speech offering peace negotiations. On 19 July Hitler made this speech to the German Parliament in Berlin, appealing "to reason and common sense", and said he could "see no reason why this war should go on". His sombre conclusion was received in silence, but he did not suggest negotiations and this was perceived as being effectively an ultimatum by the British government, which rejected the offer. Halifax kept trying to arrange peace until he was sent to Washington in December as ambassador, and in January 1941 Hitler expressed continued interest in negotiating peace with Britain.

A May 1939 planning exercise by Luftflotte 3 found that the Luftwaffe lacked the means to do much damage to Britain's war economy beyond laying naval mines.Joseph Schmid, in charge of Luftwaffe intelligence, presented a report on 22 November 1939, stating that, "Of all Germany's possible enemies, Britain is the most dangerous." This "Proposal for the Conduct of Air Warfare" argued for a counter to the British blockade and said "Key is to paralyse the British trade". Instead of the Wehrmacht attacking the French, the Luftwaffe with naval assistance was to block imports to Britain and attack seaports. "Should the enemy resort to terror measures – for example, to attack our towns in western Germany" they could retaliate by bombing industrial centres and London. Parts of this appeared on 29 November in "Directive No. 9" as future actions once the coast had been conquered. On 24 May 1940 "Directive No. 13" authorised attacks on the blockade targets, as well as retaliation for RAF bombing of industrial targets in the Ruhr.

After the defeat of France, the OKW felt they had won the war, and some more pressure would persuade Britain to give in. On 30 June, the OKW Chief of Staff Alfred Jodl issued his paper setting out options: the first was to increase attacks on shipping, economic targets and the RAF: air attacks and food shortages were expected to break morale and lead to capitulation. Destruction of the RAF was the first priority, and invasion would be a last resort. Göring's operational directive issued the same day ordered the destruction of the RAF to clear the way for attacks cutting off seaborne supplies to Britain. It made no mention of invasion.

In November 1939, the OKW reviewed the potential for an air- and seaborne invasion of Britain: the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) was faced with the threat the Royal Navy's larger Home Fleet posed to a crossing of the English Channel, and together with the German Army viewed control of airspace as a necessary precondition. The German navy thought air superiority alone was insufficient; the German naval staff had already produced a study (in 1939) on the possibility of an invasion of Britain and concluded that it also required naval superiority. The Luftwaffe said invasion could only be "the final act in an already victorious war."

Hitler first discussed the idea of an invasion at a 21 May 1940 meeting with Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, who stressed the difficulties and his own preference for a blockade. OKW Chief of Staff Jodl's 30 June report described invasion as a last resort once the British economy had been damaged and the Luftwaffe had full air superiority. On 2 July, OKW requested preliminary plans.

In Britain, Churchill described "the great invasion scare" as "serving a very useful purpose" by "keeping every man and woman tuned to a high pitch of readiness". Historian Len Deighton stated that on 10 July Churchill advised the War Cabinet that invasion could be ignored, as it "would be a most hazardous and suicidal operation".

On 11 July, Hitler agreed with Raeder that invasion would be a last resort, and the Luftwaffe advised that gaining air superiority would take 14 to 28 days. Hitler met his army chiefs, von Brauchitsch and Halder, at the Berchtesgaden on 13 July where they presented detailed plans on the assumption that the navy would provide safe transport. Von Brauchitsch and Halder were surprised that Hitler took no interest in the invasion plans, unlike his usual attitude toward military operations, but on 16 July he issued Directive No. 16, ordering preparations for Operation Sea Lion.

The navy insisted on a narrow beachhead and an extended period for landing troops; the army rejected these plans: the Luftwaffe could begin an air attack in August. Hitler held a meeting of his army and navy chiefs on 31 July. The navy said 22 September was the earliest possible date and proposed postponement until the following year, but Hitler preferred September. He then told von Brauchitsch and Halder that he would decide on the landing operation eight to fourteen days after the air attack began. On 1 August, he issued Directive No. 17 for intensified air and sea warfare, to begin with Adlertag on or after 5 August, subject to weather, keeping options open for negotiated peace or blockade and siege.

Under the continuing influence of the 1935 "Conduct of the Air War" doctrine, the main focus of the Luftwaffe command (including Göring) was in concentrating attacks to destroy enemy armed forces on the battlefield, and "blitzkrieg" close air support of the army succeeded brilliantly. They reserved strategic bombing for a stalemate situation or revenge attacks, but doubted if this could be decisive on its own and regarded bombing civilians to destroy homes or undermine morale as a waste of strategic effort.

The defeat of France in June 1940 introduced the prospect for the first time of independent air action against Britain. A July Fliegercorps I paper asserted that Germany was by definition an air power: "Its chief weapon against England is the Air Force, then the Navy, followed by the landing forces and the Army." In 1940, the Luftwaffe would undertake a "strategic offensive ... on its own and independent of the other services", according to an April 1944 German account of their military mission. Göring was convinced that strategic bombing could win objectives that were beyond the army and navy, and gain political advantages in the Third Reich for the Luftwaffe and himself. He expected air warfare to decisively force Britain to negotiate, as all in the OKW hoped, and the Luftwaffe took little interest in planning to support an invasion.

The Luftwaffe faced a more capable opponent than any it had previously met: a sizeable, highly coordinated, well-supplied, modern air force.

Fighters

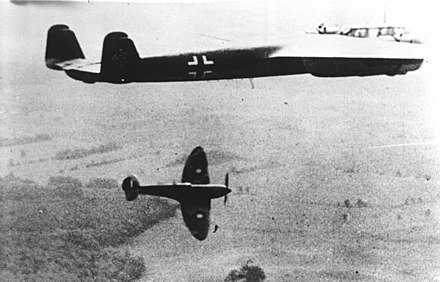

The Luftwaffe's Messerschmitt Bf 109E and Bf 110C fought against the RAF's workhorse Hurricane Mk I and the less numerous Spitfire Mk I; Hurricanes outnumbered Spitfires in RAF Fighter Command by about 2:1 when war broke out. The Bf 109E had a better climb rate and was up to 40 mph faster in level flight than the Rotol (constant speed propeller) equipped Hurricane Mk I, depending on altitude. The speed and climb disparity with the original non-Rotol Hurricane was even greater. By mid-1940, all RAF Spitfire and Hurricane fighter squadrons converted to 100 octane aviation fuel, which allowed their Merlin engines to generate significantly more power and an approximately 30 mph increase in speed at low altitudes through the use of an Emergency Boost Override. In September 1940, the more powerful Mk IIa series 1 Hurricanes started entering service in small numbers. This version was capable of a maximum speed of 342 mph (550 km/h), some 20 mph more than the original (non-Rotol) Mk I, though it was still 15 to 20 mph slower than a Bf 109 (depending on altitude).

The performance of the Spitfire over Dunkirk came as a surprise to the Jagdwaffe, although the German pilots retained a strong belief that the 109 was the superior fighter. The British fighters were equipped with eight Browning .303 (7.7mm) machine guns, while most Bf 109Es had two 20mm cannons supplemented by two 7.92mm machine guns. The former was much more effective than the .303; during the Battle it was not unknown for damaged German bombers to limp home with up to two hundred .303 hits. At some altitudes, the Bf 109 could outclimb the British fighter. It could also engage in vertical-plane negative-g manoeuvres without the engine cutting out because its DB 601 engine used fuel injection; this allowed the 109 to dive away from attackers more readily than the carburettor-equipped Merlin. On the other hand, the Bf 109E had a much larger turning circle than its two foes. In general, though, as Alfred Price noted in The Spitfire Story:

... the differences between the Spitfire and the Me 109 in performance and handling were only marginal, and in a combat they were almost always surmounted by tactical considerations of which side had seen the other first, which had the advantage of sun, altitude, numbers, pilot ability, tactical situation, tactical co-ordination, amount of fuel remaining, etc.

The Bf 109E was also used as a Jabo (jagdbomber, fighter-bomber) – the E-4/B and E-7 models could carry a 250 kg bomb underneath the fuselage, the later model arriving during the battle. The Bf 109, unlike the Stuka, could fight on equal terms with RAF fighters after releasing its ordnance.

At the start of the battle, the twin-engined Messerschmitt Bf 110C long-range Zerstörer ("Destroyer") was also expected to engage in air-to-air combat while escorting the Luftwaffe bomber fleet. Although the 110 was faster than the Hurricane and almost as fast as the Spitfire, its lack of manoeuvrability and acceleration meant that it was a failure as a long-range escort fighter. On 13 and 15 August, thirteen and thirty aircraft were lost, the equivalent of an entire Gruppe, and the type's worst losses during the campaign. This trend continued with a further eight and fifteen lost on 16 and 17 August.

The most successful role of the Bf 110 during the battle was as a Schnellbomber (fast bomber). The Bf 110 usually used a shallow dive to bomb the target and escape at high speed. One unit, Erprobungsgruppe 210 – initially formed as the service test unit (Erprobungskommando) for the emerging successor to the 110, the Me 210 – proved that the Bf 110 could still be used to good effect in attacking small or "pinpoint" targets.

The RAF's Boulton Paul Defiant had some initial success over Dunkirk because of its resemblance to the Hurricane; Luftwaffe fighters attacking from the rear were surprised by its unusual gun turret. During the Battle of Britain, it proved hopelessly outclassed. For various reasons, the Defiant lacked any form of forward-firing armament, and the heavy turret and second crewman meant it could not outrun or outmanoeuvre either the Bf 109 or Bf 110. By the end of August, after disastrous losses, the aircraft was withdrawn from daylight service.

The Luftwaffe's primary bombers were the Heinkel He 111, Dornier Do 17, and Junkers Ju 88 for level bombing at medium to high altitudes, and the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka for dive-bombing tactics. The He 111 was used in greater numbers than the others during the conflict, and was better known, partly due to its distinctive wing shape. Each level bomber also had a few reconnaissance versions accompanying them that were used during the battle.

Although it had been successful in previous Luftwaffe engagements, the Stuka suffered heavy losses in the Battle of Britain, particularly on 18 August, due to its slow speed and vulnerability to fighter interception after dive-bombing a target. As the losses went up along with their limited payload and range, Stuka units were largely removed from operations over England and diverted to concentrate on shipping instead until they were eventually re-deployed to the Eastern Front in 1941. For some raids, they were called back, such as on 13 September to attack Tangmere airfield.

The remaining three bomber types differed in their capabilities; the Dornier Do 17 was the slowest and had the smallest bomb load; the Ju 88 was the fastest once its mainly external bomb load was dropped; and the He 111 had the largest (internal) bomb load. All three bomber types suffered heavy losses from the home-based British fighters, but the Ju 88 had significantly lower loss rates due to its greater speed and its ability to dive out of trouble (it was originally designed as a dive bomber). The German bombers required constant protection by the Luftwaffe's fighter force. German escorts were not sufficiently numerous. Bf 109Es were ordered to support more than 300–400 bombers on any given day. Later in the conflict, when night bombing became more frequent, all three were used. Due to its smaller bomb load, the lighter Do 17 was used less than the He 111 and Ju 88 for this purpose.

On the British side, three bomber types were mostly used on night operations against targets such as factories, invasion ports and railway centres; the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, the Handley-Page Hampden and the Vickers Wellington were classified as heavy bombers by the RAF, although the Hampden was a medium bomber comparable to the He 111. The twin-engined Bristol Blenheim and the obsolescent single-engined Fairey Battle were both light bombers; the Blenheim was the most numerous of the aircraft equipping RAF Bomber Command and was used in attacks against shipping, ports, airfields and factories on the continent by day and by night. The Fairey Battle squadrons, which had suffered heavy losses in daylight attacks during the Battle of France, were brought up to strength with reserve aircraft and continued to operate at night in attacks against the invasion ports, until the Battle was withdrawn from UK front line service in October 1940.

Before the war, the RAF's processes for selecting potential candidates were opened to men of all social classes through the creation in 1936 of the RAF Volunteer Reserve, which "... was designed to appeal, to ... young men ... without any class distinctions ..." The older squadrons of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force did retain some of their upper-class exclusiveness, but their numbers were soon swamped by the newcomers of the RAFVR; by 1 September 1939, 6,646 pilots had been trained through the RAFVR.

By mid-1940, there were about 9,000 pilots in the RAF to man about 5,000 aircraft, most of which were bombers. Fighter Command was never short of pilots, but the problem of finding sufficient numbers of fully trained fighter pilots became acute by mid-August 1940. With aircraft production running at 300 planes each week, only 200 pilots were trained in the same period. In addition, more pilots were allocated to squadrons than there were aircraft, as this allowed squadrons to maintain operational strength despite casualties and still provide for pilot leave. Another factor was that only about 30% of the 9,000 pilots were assigned to operational squadrons; 20% of the pilots were involved in conducting pilot training, and a further 20% were undergoing further instruction, like those offered in Canada and in Southern Rhodesia to the Commonwealth trainees, although already qualified. The rest were assigned to staff positions, since RAF policy dictated that only pilots could make many staff and operational command decisions, even in engineering matters. At the height of the fighting, and despite Churchill's insistence, only 30 pilots were released to the front line from administrative duties.

For these reasons, and the permanent loss of 435 pilots during the Battle of France alone along with many more wounded, and others lost in Norway, the RAF had fewer experienced pilots at the start of the initial defence of their home. It was the lack of trained pilots in the fighting squadrons, rather than the lack of aircraft, that became the greatest concern for Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, Commander of Fighter Command. Drawing from regular RAF forces, the Auxiliary Air Force and the Volunteer Reserve, the British were able to muster some 1,103 fighter pilots on 1 July. Replacement pilots, with little flight training and often no gunnery training, suffered high casualty rates, thus exacerbating the problem.

The Luftwaffe, on the other hand, were able to muster a larger number (1,450) of more experienced fighter pilots. Drawing from a cadre of Spanish Civil War veterans, these pilots already had comprehensive courses in aerial gunnery and instructions in tactics suited for fighter-versus-fighter combat. Training manuals discouraged heroism, stressing the importance of attacking only when the odds were in the pilot's favour. Despite the high levels of experience, German fighter formations did not provide a sufficient reserve of pilots to allow for losses and leave, and the Luftwaffe was unable to produce enough pilots to prevent a decline in operational strength as the battle progressed.

International participation

About 20% of pilots who took part in the battle were from non-British countries. The Royal Air Force roll of honour for the Battle of Britain recognises 595 non-British pilots (out of 2,936) as flying at least one authorised operational sortie with an eligible unit of the RAF or Fleet Air Arm between 10 July and 31 October 1940. These included 145 Poles, 127 New Zealanders, 112 Canadians, 88 Czechoslovaks, 10 Irish, 32 Australians, 28 Belgians, 25 South Africans, 13 French, 9 Americans, 3 Southern Rhodesians and individuals from Jamaica, Barbados and Newfoundland. "Altogether in the fighter battles, the bombing raids, and the various patrols flown between 10 July and 31 October 1940 by the Royal Air Force, 1495 aircrew were killed, of whom 449 were fighter pilots, 718 aircrew from Bomber Command, and 280 from Coastal Command. Among those killed were 47 airmen from Canada, 24 from Australia, 17 from South Africa, 30 from Poland, 20 from Czechoslovakia and six from Belgium. Forty-seven New Zealanders lost their lives, including 15 fighter pilots, 24 bomber and eight coastal aircrew. The names of these Allied and Commonwealth airmen are inscribed in a memorial book that rests in the Battle of Britain Chapel in Westminster Abbey. In the chapel is a stained glass window which contains the badges of the fighter squadrons which operated during the battle and the flags of the nations to which the pilots and aircrew belonged."

These pilots, some of whom had to flee their home countries because of German invasions, fought with distinction. The No. 303 Polish Fighter Squadron for example was possibly the highest scoring of the Hurricane squadrons. "Had it not been for the magnificent material contributed by the Polish squadrons and their unsurpassed gallantry," wrote Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, head of RAF Fighter Command, "I hesitate to say that the outcome of the Battle would have been the same."

An element of the Italian Royal Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) called the Italian Air Corps (Corpo Aereo Italiano or CAI) first saw action in late October 1940. It took part in the latter stages of the battle but achieved limited success. The unit was redeployed in early 1941.

The indecision of OKL over what to do was reflected in shifts in Luftwaffe strategy. The doctrine of concentrated close air support of the army at the battlefront succeeded against Poland, Denmark and Norway, the Low Countries and France but incurred significant losses. The Luftwaffe had to build or repair bases in the conquered territories, and rebuild their strength. In June 1940 they began regular armed reconnaissance flights and sporadic Störangriffe, nuisance raids of one or a few bombers by day and night. These gave crews practice in navigation and avoiding air defences and set off air raid alarms which disturbed civilian morale. Similar nuisance raids continued throughout the battle, into late 1940. Scattered naval mine-laying sorties began at the outset and increased gradually over the battle period.

Göring's operational directive of 30 June ordered the destruction of the RAF, including the aircraft industry, to end RAF bombing raids on Germany and facilitating attacks on ports and storage in the Luftwaffe blockade of Britain. Attacks on Channel shipping in the Kanalkampf began on 4 July, and were formalised on 11 July in an order by Hans Jeschonnek which added the arms industry as a target. On 16 July, Directive No. 16 ordered preparations for Operation Sea Lion and on the next day the Luftwaffe was ordered to stand by in full readiness. Göring met his air fleet commanders and on 24 July issued orders for gaining air supremacy, protecting the army and navy if the invasion went ahead and attacking Royal Navy ships and continuing the blockade. Once the RAF had been defeated, Luftwaffe bombers were to move forward beyond London without the need for fighter escort, destroying military and economic targets.

At a meeting on 1 August the command reviewed plans produced by each Fliegerkorps with differing proposals for targets including whether to bomb airfields but failed to decide a priority. Intelligence reports gave Göring the impression that the RAF was almost defeated, raids would attract British fighters for the Luftwaffe to shoot down. On 6 August he finalised plans for Adlertag (Eagle Day) with Kesselring, Sperrle and Stumpff; the destruction of RAF Fighter Command in the south of England was to take four days, with lightly escorted small bomber raids leaving the main fighter force free to attack RAF fighters. Bombing of military and economic targets was then to systematically extend up to the Midlands until daylight attacks could proceed unhindered over the whole of Britain.

Bombing of London was to be held back while these night time "destroyer" attacks proceeded over other urban areas, then, in the culmination of the campaign, a major attack on the capital was intended to cause a crisis, with refugees fleeing London just as Operation Sea Lion was to begin. With hopes fading for the possibility of invasion, on 4 September Hitler authorised a main focus on day and night attacks on tactical targets, with London as the main target, which became known as the Blitz. With increasing difficulty in defending bombers in day raids, the Luftwaffe shifted to a strategic bombing campaign of night raids aiming to overcome British resistance by damaging infrastructure and food stocks, though intentional terror bombing of civilians was not sanctioned.

The Luftwaffe regrouped after the Battle of France into three Luftflotten (Air Fleets) opposite Britain's southern and eastern coasts. Luftflotte 2 (Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring), was responsible for the bombing of south-east England and the London area. Luftflotte 3 (Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle) concentrated on the West Country, Wales, the Midlands and north-west England. Luftflotte 5 (Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff) from his headquarters in Norway, attacked the north of England and Scotland. As the battle progressed, command responsibility shifted, with Luftflotte 3 taking more responsibility for the night bombing and the main daylight operations fell upon Luftflotte 2.

Initial Luftwaffe estimates were that it would take four days to defeat RAF Fighter Command in southern England. This would be followed by a four-week offensive during which the bombers and long-range fighters would destroy all military installations throughout the country and wreck the British aircraft industry. The campaign was planned to begin with attacks on airfields near the coast, gradually moving inland to attack the ring of sector airfields defending London. Later reassessments gave the Luftwaffe five weeks, from 8 August to 15 September, to establish temporary air superiority over England. Fighter Command had to be destroyed, either on the ground or in the air, yet the Luftwaffe had to preserve its strength to be able to support the invasion; the Luftwaffe had to maintain a high "kill ratio" over the RAF fighters. The only alternative to the goal of air superiority was a terror bombing campaign aimed at the civilian population but this was considered a last resort and it was forbidden by Hitler. The Luftwaffe kept broadly to this scheme but its commanders had differences of opinion on strategy. Sperrle wanted to eradicate the air defence infrastructure by bombing it. Kesselring championed attacking London directly – either to bombard the British government into submission or to draw RAF fighters into a decisive battle. Göring did nothing to resolve this disagreement between his commanders and gave only vague directives during the initial stages of the battle, Göring seemingly unable to decide upon which strategy to pursue.

Luftwaffe formations employed a loose section of two (nicknamed the Rotte [pack]), based on a leader (Rottenführer) followed at a distance of about 200 m (220 yd) by his wingman, Rottenhund pack dog or Katschmarek, the turning radius of a Bf 109, enabling both aircraft to turn together at high speed. The Katschmarek flew slightly higher and was trained always to stay with his leader. With more room between them, both could spend less time maintaining formation and more time looking around and covering each other's blind spots. Attacking aircraft could be sandwiched between the two 109s. The formation was developed from principles formulated by the First World War ace Oswald Boelcke in 1916. In 1934 the Finnish Air Force adopted similar formations, called partio (patrol; two aircraft) and parvi (two patrols; four aircraft), for similar reasons, though Luftwaffe pilots during the Spanish Civil War (led by Günther Lützow and Werner Mölders, among others) are generally given credit. The Rotte allowed the Rottenführer to concentrate on shooting down aircraft but few wingmen had the chance, leading to some resentment in the lower ranks where it was felt that the high scores came at their expense. Two Rotten combined as a Schwarm, where all the pilots could watch what was happening around them. Each Schwarm in a Staffel flew at staggered heights and with about 200 m (220 yd) between them, making the formation difficult to spot at longer ranges and allowing for a great deal of flexibility. By using a tight "cross-over" turn, a Schwarm could quickly change direction.

The Bf 110s adopted the same Schwarm formation as the 109s but were seldom able to use this to the same advantage. The Bf 110's most successful method of attack was the "bounce" from above. When attacked, Zerstörergruppen increasingly resorted to forming large defensive circles, where each Bf 110 guarded the tail of the aircraft ahead of it. Göring ordered that they be renamed "offensive circles" in a vain bid to improve rapidly declining morale. These conspicuous formations were often successful in attracting RAF fighters that were sometimes "bounced" by high-flying Bf 109s. This led to the often repeated misconception that the Bf 110s were escorted by Bf 109s.

Luftwaffe tactics were influenced by their fighters. The Bf 110 proved too vulnerable against the nimble single-engined RAF fighters and the bulk of fighter escort duties devolved to the Bf 109. Fighter tactics were then complicated by bomber crews who demanded closer protection. After the hard-fought battles of 15 and 18 August, Göring met his unit leaders. The need for the fighters to meet up on time with the bombers was stressed. It was also decided that one bomber Gruppe could only be properly protected by several Gruppen of 109s. Göring stipulated that as many fighters as possible were to be left free for Freie Jagd ("Free Hunts": a free-roving fighter sweep preceded a raid to try to sweep defenders out of the raid's path). The Ju 87 units, which had suffered heavy casualties, were only to be used under favourable circumstances. In early September, due to increasing complaints from the bomber crews about RAF fighters seemingly able to get through the escort screen, Göring ordered an increase in close escort duties. This decision shackled many of the Bf 109s to the bombers and although they were more successful at protecting the bombers, casualties amongst the fighters mounted primarily because they were forced to fly and manoeuvre at reduced speeds.

The Luftwaffe varied its tactics to break Fighter Command. It launched many Freie Jagd to draw up RAF fighters. RAF fighter controllers were often able to detect these and position squadrons to avoid them, keeping to Dowding's plan to preserve fighter strength for the bomber formations. The Luftwaffe also tried using small formations of bombers as bait, covering them with large numbers of escorts. This was more successful but escort duty tied the fighters tied to the slower bombers making them more vulnerable.

By September, standard tactics for raids had become an amalgam of techniques. A Freie Jagd would precede the main attack formations. The bombers would fly in at altitudes between 5,000 and 6,000 m (16,000 and 20,000 ft), closely escorted by fighters. Escorts were divided into two parts (usually Gruppen), some operating close to the bombers and others a few hundred yards away and a little above. If the formation was attacked from the starboard, the starboard section engaged the attackers, the top section moving to starboard and the port section to the top position. If the attack came from the port side the system was reversed. British fighters coming from the rear were engaged by the rear section and the two outside sections similarly moving to the rear. If the threat came from above, the top section went into action while the side sections gained height to be able to follow RAF fighters down as they broke away. If attacked, all sections flew in defensive circles. These tactics were skilfully evolved and carried out and were difficult to counter.

Adolf Galland noted:

We had the impression that, whatever we did, we were bound to be wrong. Fighter protection for bombers created many problems which had to be solved in action. Bomber pilots preferred close screening in which their formation was surrounded by pairs of fighters pursuing a zigzag course. Obviously, the visible presence of the protective fighters gave the bomber pilots a greater sense of security. However, this was a faulty conclusion, because a fighter can only carry out this purely defensive task by taking the initiative in the offensive. He must never wait until attacked because he then loses the chance of acting. We fighter pilots certainly preferred the free chase during the approach and over the target area. This gives the greatest relief and the best protection for the bomber force.

The biggest disadvantage faced by Bf 109 pilots was that without the benefit of long-range drop tanks (which were introduced in limited numbers in the late stages of the battle), usually of 300 l (66 imp gal; 79 US gal) capacity, the 109s had an endurance of just over an hour and, for the 109E, a 600 km (370 mi) range. Once over Britain, a 109 pilot had to keep an eye on a red "low fuel" light on the instrument panel: once this was illuminated, he was forced to turn back and head for France. With the prospect of two long flights over water and knowing their range was substantially reduced when escorting bombers or during combat, the Jagdflieger coined the term Kanalkrankheit or "Channel sickness".

Intelligence

The Luftwaffe was ill-served by its lack of military intelligence about the British defences. The German intelligence services were fractured and plagued by rivalry; their performance was "amateurish". By 1940, there were few German agents operating in Great Britain and a handful of bungled attempts to insert spies into the country were foiled.

As a result of intercepted radio transmissions, the Germans began to realise that the RAF fighters were being controlled from ground facilities; in July and August 1939, for example, the airship Graf Zeppelin, which was packed with equipment for listening in on RAF radio and RDF transmissions, flew around the coasts of Britain. Although the Luftwaffe correctly interpreted these new ground control procedures, they were incorrectly assessed as being rigid and ineffectual. A British radar system was well known to the Luftwaffe from intelligence gathered before the war, but the highly developed "Dowding system" linked with fighter control had been a well-kept secret. Even when good information existed, such as a November 1939 Abwehr assessment of Fighter Command strengths and capabilities by Abteilung V, it was ignored if it did not match conventional preconceptions.

On 16 July 1940, Abteilung V, commanded by Oberstleutnant "Beppo" Schmid, produced a report on the RAF and on Britain's defensive capabilities which was adopted by the frontline commanders as a basis for their operational plans. One of the most conspicuous failures of the report was the lack of information on the RAF's RDF network and control systems capabilities; it was assumed that the system was rigid and inflexible, with the RAF fighters being "tied" to their home bases. An optimistic and, as it turned out, erroneous conclusion reached was:

D. Supply Situation... At present the British aircraft industry produces about 180 to 300 first line fighters and 140 first line bombers a month. In view of the present conditions relating to production (the appearance of raw material difficulties, the disruption or breakdown of production at factories owing to air attacks, the increased vulnerability to air attack owing to the fundamental reorganisation of the aircraft industry now in progress), it is believed that for the time being output will decrease rather than increase. In the event of an intensification of air warfare it is expected that the present strength of the RAF will fall, and this decline will be aggravated by the continued decrease in production.

Because of this statement, reinforced by another more detailed report, issued on 10 August, there was a mindset in the ranks of the Luftwaffe that the RAF would run out of frontline fighters. The Luftwaffe believed it was weakening Fighter Command at three times the actual attrition rate. Many times, the leadership believed Fighter Command's strength had collapsed, only to discover that the RAF were able to send up defensive formations at will.

Throughout the battle, the Luftwaffe had to use numerous reconnaissance sorties to make up for the poor intelligence. Reconnaissance aircraft (initially mostly Dornier Do 17s, but increasingly Bf 110s) proved easy prey for British fighters, as it was seldom possible for them to be escorted by Bf 109s. Thus, the Luftwaffe operated "blind" for much of the battle, unsure of its enemy's true strengths, capabilities, and deployments. Many of the Fighter Command airfields were never attacked, while raids against supposed fighter airfields fell instead on bomber or coastal defence stations. The results of bombing and air fighting were consistently exaggerated, due to inaccurate claims, over-enthusiastic reports and the difficulty of confirmation over enemy territory. In the euphoric atmosphere of perceived victory, the Luftwaffe leadership became increasingly disconnected from reality. This lack of leadership and solid intelligence meant the Germans did not adopt a consistent strategy, even when the RAF had its back to the wall. Moreover, there was never a systematic focus on one type of target (such as airbases, radar stations, or aircraft factories); consequently, the already haphazard effort was further diluted.

Navigational aids

While the British were using radar for air defence more effectively than the Germans realised, the Luftwaffe attempted to press its own offensive with advanced radio navigation systems of which the British were initially not aware. One of these was Knickebein ("bent leg"); this system was used at night and for raids where precision was required. It was rarely used during the Battle of Britain.

Air-sea rescue

The Luftwaffe was much better prepared for the task of air-sea rescue than the RAF, specifically tasking the Seenotdienst unit, equipped with about 30 Heinkel He 59 floatplanes, with picking up downed aircrew from the North Sea, English Channel and the Dover Straits. In addition, Luftwaffe aircraft were equipped with life rafts and the aircrew were provided with sachets of a chemical called fluorescein which, on reacting with water, created a large, easy-to-see, bright green patch. In accordance with the Geneva Convention, the He 59s were unarmed and painted white with civilian registration markings and red crosses. Nevertheless, RAF aircraft attacked these aircraft, as some were escorted by Bf 109s.

After single He 59s were forced to land on the sea by RAF fighters, on 1 and 9 July respectively, a controversial order was issued to the RAF on 13 July; this stated that from 20 July, Seenotdienst aircraft were to be shot down. One of the reasons given by Churchill was:

We did not recognise this means of rescuing enemy pilots so they could come and bomb our civil population again ... all German air ambulances were forced down or shot down by our fighters on definite orders approved by the War Cabinet.

The British also believed that their crews would report on convoys, the Air Ministry issuing a communiqué to the German government on 14 July that Britain was

unable, however, to grant immunity to such aircraft flying over areas in which operations are in progress on land or at sea, or approaching British or Allied territory, or territory in British occupation, or British or Allied ships. Ambulance aircraft which do not comply with the above will do so at their own risk and peril

The white He 59s were soon repainted in camouflage colours and armed with defensive machine guns. Although another four He 59s were shot down by RAF aircraft, the Seenotdienst continued to pick up downed Luftwaffe and Allied aircrew throughout the battle, earning praise from Adolf Galland for their bravery.

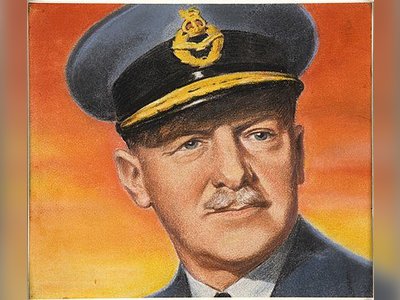

Commander-in-Chief, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding

10 Group Commander, Sir Quintin Brand

11 Group Commander, Keith Park

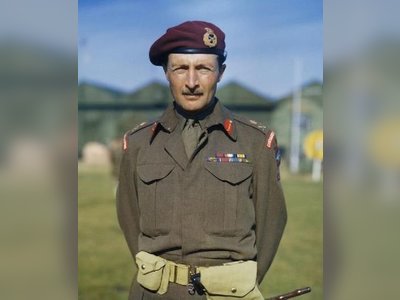

12 Group Commander, Trafford Leigh-Mallory

13 Group Commander, Richard Saul

During early tests of the Chain Home system, the slow flow of information from the CH radars and observers to the aircraft often caused them to miss their "bandits". The solution, today known as the "Dowding system", was to create a set of reporting chains to move information from the various observation points to the pilots in their fighters. It was named after its chief architect, "Stuffy" Dowding.

Reports from CH radars and the Observer Corps were sent directly to Fighter Command Headquarters (FCHQ) at Bentley Priory where they were "filtered" to combine multiple reports of the same formations into single tracks. Telephone operators would then forward only the information of interest to the Group headquarters, where the map would be re-created. This process was repeated to produce another version of the map at the Sector level, covering a much smaller area. Looking over their maps, Group level commanders could select squadrons to attack particular targets. From that point, the Sector operators would give commands to the fighters to arrange an interception, as well as return them to base. Sector stations also controlled the anti-aircraft batteries in their area; an army officer sat beside each fighter controller and directed the gun crews when to open and cease fire.

The Dowding system dramatically improved the speed and accuracy of the information that flowed to the pilots. During the early war period, it was expected that an average interception mission might have a 30% chance of ever seeing their target. During the battle, the Dowding system maintained an average rate over 75%, with several examples of 100% rates – every fighter dispatched found and intercepted its target. In contrast, Luftwaffe fighters attempting to intercept raids had to randomly seek their targets and often returned home having never seen enemy aircraft. The result is what is now known as an example of "force multiplication"; RAF fighters were as effective as two or more Luftwaffe fighters, greatly offsetting, or overturning, the disparity in actual numbers.

While Luftwaffe intelligence reports underestimated British fighter forces and aircraft production, the British intelligence estimates went the other way: they overestimated German aircraft production, numbers and range of aircraft available, and numbers of Luftwaffe pilots. In action, the Luftwaffe believed from their pilot claims and the impression given by aerial reconnaissance that the RAF was close to defeat, and the British made strenuous efforts to overcome the perceived advantages held by their opponents.

It is unclear how much the British intercepts of the Enigma cipher, used for high-security German radio communications, affected the battle. Ultra, the information obtained from Enigma intercepts, gave the highest echelons of the British command a view of German intentions. According to F. W. Winterbotham, who was the senior Air Staff representative in the Secret Intelligence Service, Ultra helped establish the strength and composition of the Luftwaffe's formations, the aims of the commanders and provided early warning of some raids. In early August it was decided that a small unit would be set up at FCHQ, which would process the flow of information from Bletchley and provide Dowding only with the most essential Ultra material; thus the Air Ministry did not have to send a continual flow of information to FCHQ, preserving secrecy, and Dowding was not inundated with non-essential information. Keith Park and his controllers were also told about Ultra. In a further attempt to camouflage the existence of Ultra, Dowding created a unit named No. 421 (Reconnaissance) Flight RAF. This unit (which later became No. 91 Squadron RAF), was equipped with Hurricanes and Spitfires and sent out aircraft to search for and report Luftwaffe formations approaching England. In addition, the radio listening service (known as Y Service), monitoring the patterns of Luftwaffe radio traffic contributed considerably to the early warning of raids.

In the late 1930s, Fighter Command expected to face only bombers over Britain, not single-engined fighters. A series of "Fighting Area Tactics" were formulated and rigidly adhered to, involving a series of manoeuvres designed to concentrate a squadron's firepower to bring down bombers. RAF fighters flew in tight, v-shaped sections ("vics") of three aircraft, with four such "sections" in tight formation. Only the squadron leader at the front was free to watch for the enemy; the other pilots had to concentrate on keeping station. Training also emphasised by-the-book attacks by sections breaking away in sequence. Fighter Command recognised the weaknesses of this structure early in the battle, but it was felt too risky to change tactics during the battle because replacement pilots – often with only minimal flying time – could not be readily retrained, and inexperienced pilots needed firm leadership in the air only rigid formations could provide. German pilots dubbed the RAF formations Idiotenreihen ("rows of idiots") because they left squadrons vulnerable to attack.

Front line RAF pilots were acutely aware of the inherent deficiencies of their own tactics. A compromise was adopted whereby squadron formations used much looser formations with one or two "weavers" flying independently above and behind to provide increased observation and rear protection; these tended to be the least experienced men and were often the first to be shot down without the other pilots even noticing that they were under attack. During the battle, 74 Squadron under Squadron Leader Adolph "Sailor" Malan adopted a variation of the German formation called the "fours in line astern", which was a vast improvement on the old three aircraft "vic". Malan's formation was later generally used by Fighter Command.

The weight of the battle fell upon 11 Group. Keith Park's tactics were to dispatch individual squadrons to intercept raids. The intention was to subject incoming bombers to continual attacks by relatively small numbers of fighters and try to break up the tight German formations. Once formations had fallen apart, stragglers could be picked off one by one. Where multiple squadrons reached a raid the procedure was for the slower Hurricanes to tackle the bombers while the more agile Spitfires held up the fighter escort. This ideal was not always achieved, resulting in occasions when Spitfires and Hurricanes reversed roles. Park also issued instructions to his units to engage in frontal attacks against the bombers, which were more vulnerable to such attacks. Again, in the environment of fast-moving, three-dimensional air battles, few RAF fighter units were able to attack the bombers from head-on.

During the battle, some commanders, notably Leigh-Mallory, proposed squadrons be formed into "Big Wings," consisting of at least three squadrons, to attack the enemy en masse, a method pioneered by Douglas Bader.

Proponents of this tactic claimed interceptions in large numbers caused greater enemy losses while reducing their own casualties. Opponents pointed out the big wings would take too long to form up, and the strategy ran a greater risk of fighters being caught on the ground refuelling. The big wing idea also caused pilots to overclaim their kills, due to the confusion of a more intense battle zone. This led to the belief big wings were far more effective than they actually were.

The issue caused intense friction between Park and Leigh-Mallory, as 12 Group was tasked with protecting 11 Group's airfields whilst Park's squadrons intercepted incoming raids. The delay in forming up Big Wings meant the formations often did not arrive at all or until after German bombers had hit 11 Group's airfields. Dowding, to highlight the problem of the Big Wing's performance, submitted a report compiled by Park to the Air Ministry on 15 November. In the report, he highlighted that during the period of 11 September – 31 October, the extensive use of the Big Wing had resulted in just 10 interceptions and one German aircraft destroyed, but his report was ignored. Post-war analysis agrees Dowding and Park's approach was best for 11 Group.

Dowding's removal from his post in November 1940 has been blamed on this struggle between Park and Leigh-Mallory's daylight strategy. The intensive raids and destruction wrought during the Blitz damaged both Dowding and Park in particular, for the failure to produce an effective night-fighter defence system, something for which the influential Leigh-Mallory had long criticised them.

Bomber Command and Coastal Command aircraft flew offensive sorties against targets in Germany and France during the battle. An hour after the declaration of war, Bomber Command launched raids on warships and naval ports by day, and in night raids dropped leaflets as it was considered illegal to bomb targets which could affect civilians. After the initial disasters of the war, with Vickers Wellington bombers shot down in large numbers attacking Wil

- Battle of Britainen.wikipedia.org